In the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, we froze the position of the nuclei to find the electronic energy. The position of the nuclei was considered as a parameter that can be modified and we were able to construct the Lenard-Jones potential for the liaisons or the surface (or hypersurface) of potential energy for molecules with more than one liaison. We will now discuss in further details about the vibration and rotation modes of molecules ant thus incorporate the movements of nuclei in the model.

The first step is to choose the set of coordinates in which we will work. A molecule with M nuclei has 3M coordinates: (xi,yi,zi) for each of the M atoms.

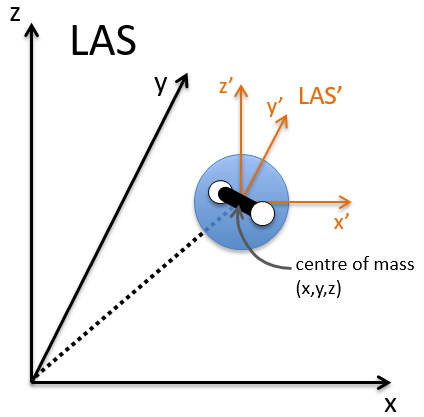

The laboratory axes system (LAS) is the first set of coordinates that we use. In this system we determine the position of the centre of mass of the molecule. Those 3 coordinates allow us to determine the translation of the molecule but not the rotation or the vibration modes: the centre of mass doesn’t move because of those modes.

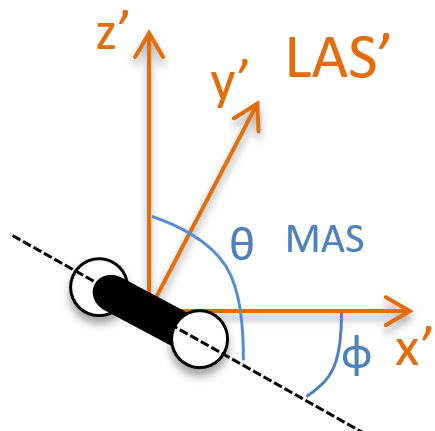

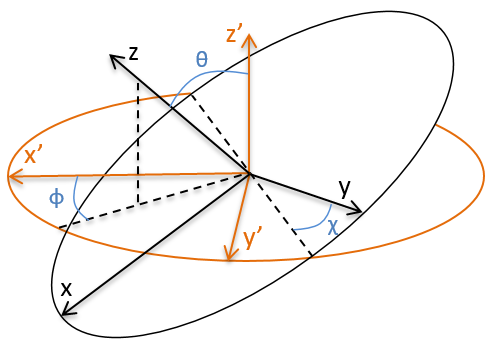

To determine those modes, we need two other sets of coordinates: the LAS’ that is fixed to the centre of mass of the molecule and consequently is independent of the translation and the MAS: molecular axes system that is fixed to the molecule and turns with it. 2 angles 0≤θ≤π and 0≤Φ≤2π are used to locate the linear molecules and a third one 0≤χ≤2π is needed for the nonlinear molecules. Those 3 angles are called the angles of Euler and are

From the 3M coordinates, we used 5 (linear molecules) or 6 (non-linear molecules). The rest correspond to the modes of vibration of the molecule. In a diatomic molecule, there will be only one mode of vibration: M=2 and 5 coordinates are used to locate it.

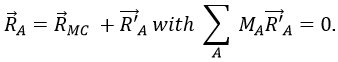

To resume, the coordinates of one molecule are given by the vector

with 3M dimensions. The translation of the centre of mass is determined in the LAS

The condition here reflects the facts that the centre of mass does not move in the LAS’ referent. The MAS rotates with the molecule. To move into this referent, we apply the matrix S to the vector RA’.

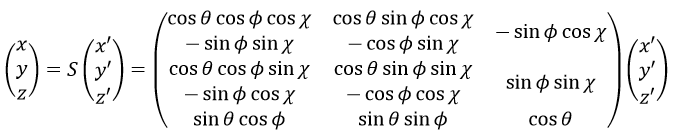

The matrix S defines the orientation of the axes (x’,y’,z’) of the LAS’ from the coordinates (x,y,z) of the LAS:

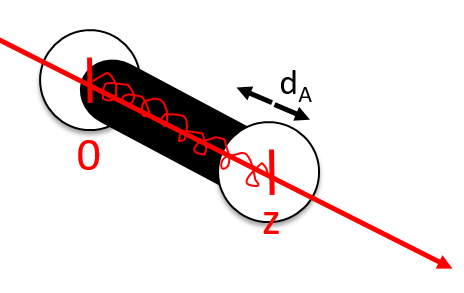

Small vibrations around the equilibrium RAeq are given by the vector dA

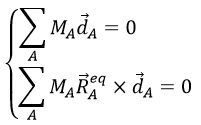

with the conditions of Eckart that

The first condition reflects that the centre of mass does not move because of the vibration and the second condition that there is no rotation in the MAS.

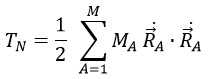

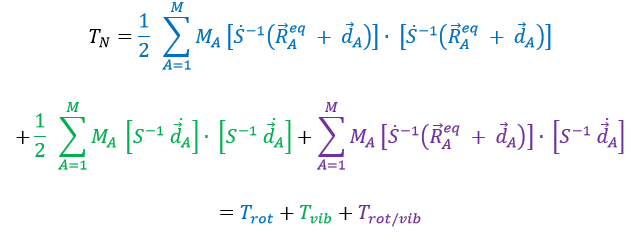

The kinetic energy of the molecule is in this notation

with MA the mass of the nucleus A and ṘA=dRA/dt. Replacing ṘA by its expression

![]()

We obtain (the red terms equal zero)

If Eckart is respected, then the interaction term Trot/vib can be neglected. We can thus approximate that the energies of rotation and of vibration are separable. The order of magnitude is indeed different: the vibration is found into the infrared while the rotation is observed in the microwave range.

Vibration

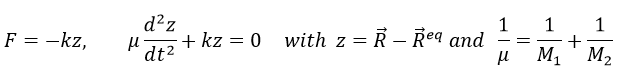

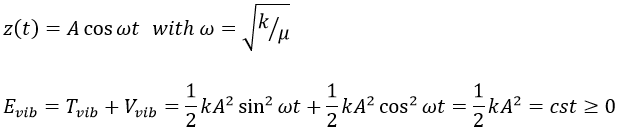

For a diatomic molecule, the oscillation is characterised by a force of recall

We find that

The energy of vibration can thus be approximated to a constant. The kinetic energy Tvib is always positive and is thus equal to

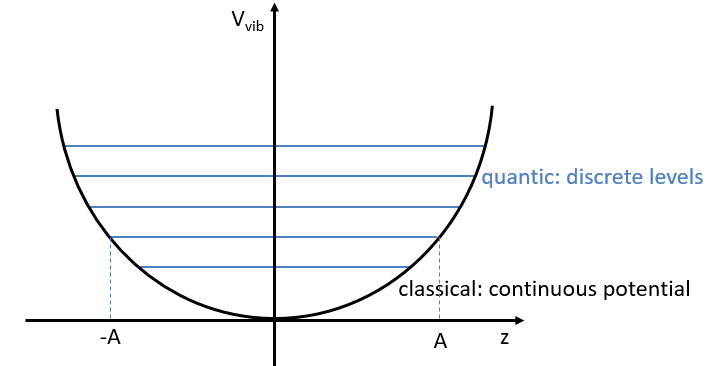

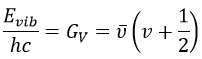

From the quantum mechanics, we know that

The separation in energy between the levels characterised by a number of nodes v=0, 1, 2, … There is thus regular a ΔGV=ῡ.

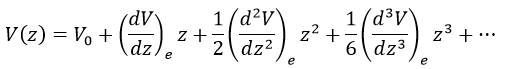

There is however a deviation to the harmonicity that we found. If we develop the potential as a series of Taylor, we obtain

The two first terms are simply equal to zero (V0=0 and the potential is at a minimum at the equilibrium). The third term is the harmonic result that we just obtained but further terms express the deviation to the harmonicity. The potential of Morse gives an empiric formula that fits correctly the real potential.

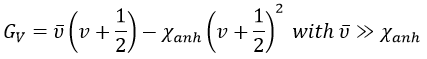

The anharmonicity modifies slightly the energy of the states

In the case of polyatomic molecules, we can consider that all the nuclei oscillate in phase, giving a base of 3M-6(5) independent movements. The result doesn’t noticeably differ from the diatomic molecule in this case.

Rotation

The rotation can be considered as a rigid rotation: the difference of frequency and of energy between the rotation and the vibrations is huge enough to make this approximation. The angular speed ω is thus identical for all the nuclei of the molecule.

The kinetic energy due to the rotation for a diatomic molecule is thus

with I the moment of inertia that is common to the two atoms.

μ is the reduced mass of the molecule. The angular moment J is given by

Its absolute value is

For a diatomic molecule, we get

The angular moment and the kinetic energy are thus directly bound:

We can go from the classical mechanics to the quantum mechanics by the application of the Hamiltonian on a wave function.

The multiplicity is gJ=2J+1. A small correction has to be added due to the centrifugal distortion, correction which is normally very small and negligible except when the rotation is very fast:

The spectrum of the rotation is thus composed of bands regularly spaced.