New treatment of irritable bowel syndrome by autonomic nervous system remodeling :

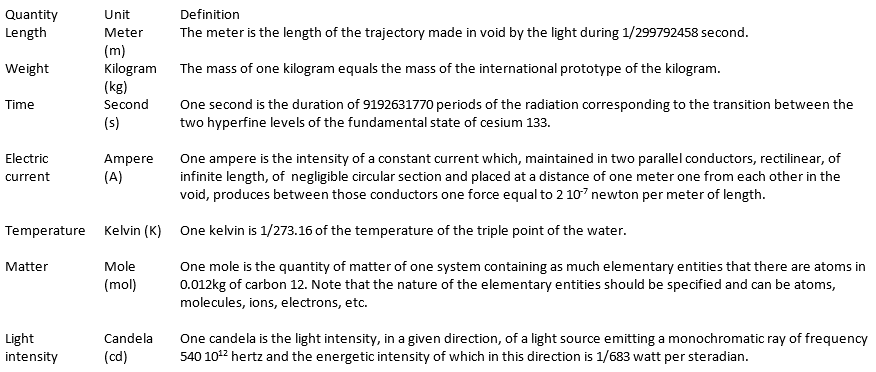

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), is classified as a functional gastrointestinal disease. Autonomic nervous system remodeling by limbic rehabilitation is a very sophisticated technique allowing a physiological treatment of bowel diseases . In cases of “pure irritable bowel syndrome” the efficiency of the treatment is now confirmed (hundreds of patients successfully treated) it’s also the same in IBS associated with nonspecific colitis. Now we begin to try successfully the IBD patients. To understand the efficacy of this technic we must begin to study the etiology and the exact mechanism leading to these abnormalities. IBS, is a chronic condition of the lower gastrointestinal tract that affects as many as 15% of adults in the world. Not easily characterized by structural abnormalities, infection, or metabolic disturbances, the underlying mechanisms of IBS remained for many years unclear.Recent research, however, has lead to an increased understanding of IBS. As a result, IBS is often referred to as spastic, nervous or irritable colon. Its hallmark is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with a change in the consistency and/or frequency of bowel movements.

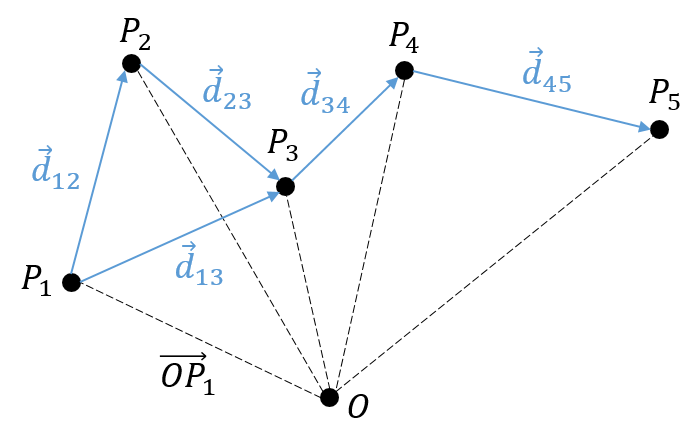

The frequency of IBS in any given population depends, in part, on the ethnic and cultural background of the population being studied, and the criteria used to diagnose the disease. Eight to 20% of adults in the Western world report symptoms consistent with IBS (approximately 65% of these are women). Asia and Africa have similar rates to those in the Western world in general. In India IBS is more common among men, although it is possible that this is a result of differences in symptom reporting and health care use between genders.

The symptoms of IBS may include abdominal pain, distention, bloating, indigestion and various symptoms of defecation. There are three subcategories of IBS, according to the principal symptoms. These are pain associated with diarrhea; pain associated with constipation; and pain and diarrhea alternating with constipation. IBS is not a psychiatric disorder, although it is tied to emotional and social stress, which can affect both the onset and severity of symptoms. IBS patients suffer from a disproportionately higher rate of co-morbidity with other disorders, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, pelvic pain and psychiatric disorders. The primary features of the syndrome include motility, sensation and central nervous system dysfunction. Motility dysfunction may be manifest in muscle spasms; contractions can be very slow or fast. An increased sensitivity to stimuli causes pain and abdominal discomfort. Researchers also suspect that the regulatory conduit between the central and enteric pathway in patients suffering from IBS may be impaired. Research suggests that many patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome have disorganized and appreciably more intense colonic contractions than normal controls.

Pathophysiology :

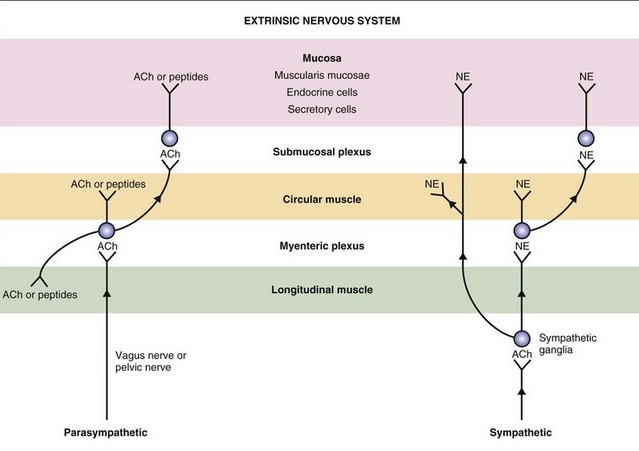

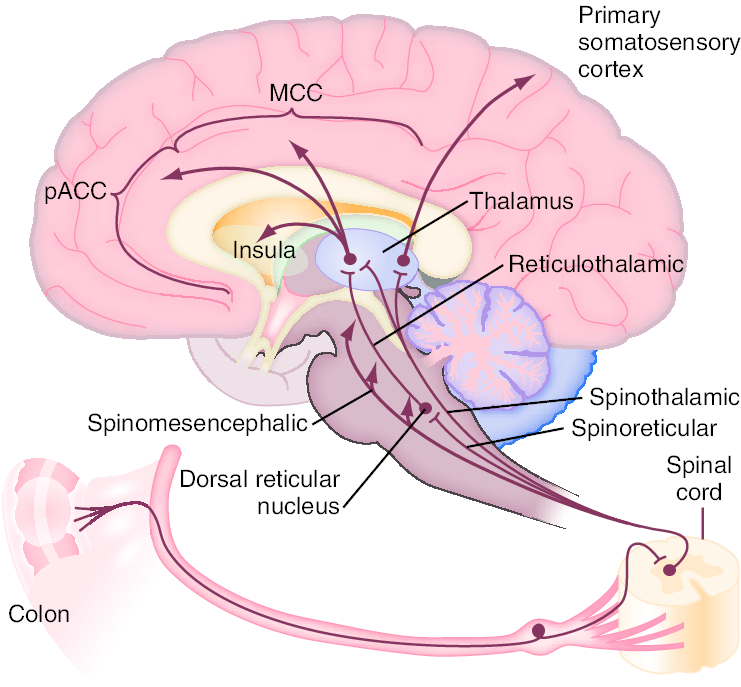

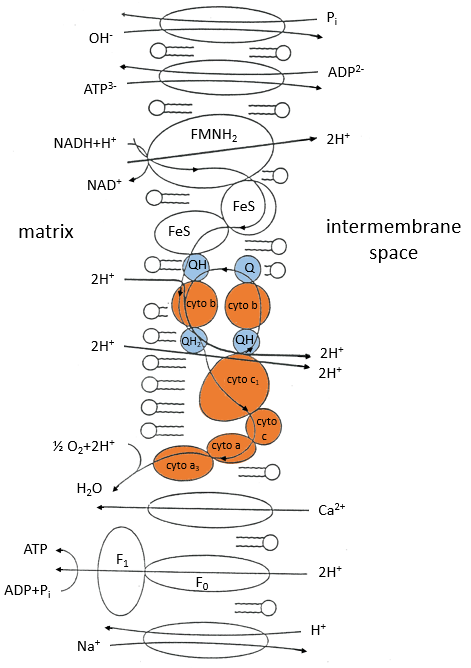

Enteric propulsion and sensation are, in part, mediated by acetylcholine and serotonin (5HT). The physiology of sensation in the gut is multifaceted. Entero-endocrine cells transmit mechanical and chemical messages. The communication between gut and brain results in reflex responses mediated at three levels—prevertebral ganglia, spinal cord and brainstem. 5-HT, substance P, CGRP, norepinephrine, kappa opiate and nitric oxide are all involved in the perception and autonomic response to visceral stimulation. Sensation is conveyed from the viscus to the conscious perception via neurons in vagal and parasympathetic fibers. Afferent nerves in the dorsal root ganglion synapse with neurons in the dorsal horn. These signals result in reflexes that control motor and secretory functions as they synapse with efferent paths in the prevertebral ganglia and spinal cord. Pain is processed through spinal afferents in the dorsal horn. Ultimately, stimulation of the brainstem brings sensation to a conscious level :

Bidirectional signaling between the brainstem and the dorsal horn mediate sensation. The descending pathways are primarily adrenergic and serotonergic and affect incoming stimuli. End organ sensitivity, stimulus intensity changes or receptive field size of the dorsal horn neuron and limbic system modulation are the mechanisms involved in visceral hypersensitivity. Enteric inflammatory cells may also play an important role in the pathophysiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinicians have for many years recognized that the onset of IBS often follows an episode of acute gastroenteritis. Inflammation may alter intestinal cytokine milieu and motility, both of which can result in an increase in a patient’s pain sensation. The menstrual cycle may also affect gut sensation and motility. Other factors, such as malabsorption of sugars (lactose, fructose, and sorbitol), probably aggravate underlying IBS, rather than serving as root causes of the disorder. In patients with rapid transit times, short or medium chain fatty acids can reach the right colon and cause diarrhea.

Symptoms:

The hallmark of IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with either a change in bowel habits or disordered defecation. The pain or discomfort associated with IBS is often poorly localized and may be migratory and variable. It may occur after a meal, during stress or at the time of menses. In addition to pain and discomfort, altered bowel habits are common, including diarrhea, constipation, and diarrhea alternating with constipation. Patients also complain of bloating or abdominal distension, mucous in the stool, urgency, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Some patients describe frequent episodes, whereas others describe long symptom-free periods. Patients with irritable bowel frequently report symptoms of other functional gastrointestinal disorders as well, including chest pain, heartburn, nausea or dyspepsia, difficulty swallowing, or a sensation of a lump in the throat or closing of the throat. Patients with IBS are generally classified according to the type of bowel habits that accompany pain. Some patients have diarrhea-predominant symptomatology, others constipation-predominant, and still others have a combination of the two. Some patients alternate between different subgroups. Symptoms may vary from barely noticeable to debilitating, at times within the same patient. In some patients, stress or life crises may be associated with the onset of symptoms, which may then disappear when the stress dissipates. Other patients seem to have random IBS episodes with spontaneous remissions. Still others describe long periods of symptoms and long symptom-free periods. In general, the symptoms of IBS wax and wane throughout life, but the majority of patients seen by physicians is 20–50 years old. In approximately 50% of patients, symptoms begin before age 35. The disorder is also recognized in children, generally appearing in early adolescence. Many patients can trace the onset of symptoms back to childhood. The prevalence of IBS is slightly lower in the elderly, and in this patient population organic disorders must be excluded. Extraintestinal symptoms are common in patients with IBS. These may include headache, sleep disturbances, post-traumatic stress disorder, temporomandibular joint disorder, sicca syndrome, back/pelvic pain, myalgias, back pain, and chronic pelvic pain. Fibromyalgia and interstitial cystitis are also frequently encountered in patients with IBS. In fact, Fibromyalgia occurs in up to 33% of patients with IBS and almost half of patients with fibromyalgia also have IBS.

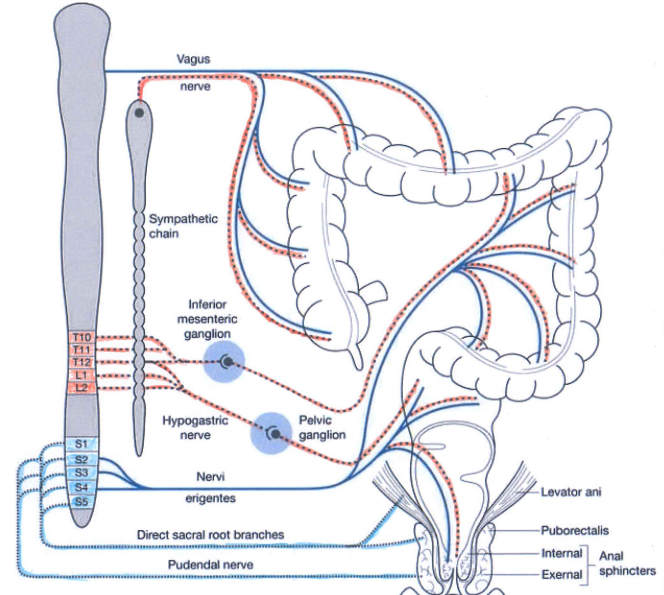

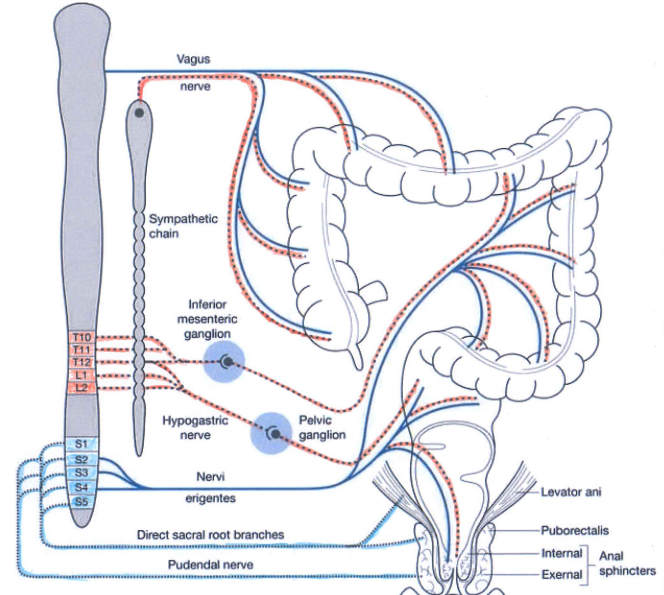

The autonomic nervous systems and the bowel:

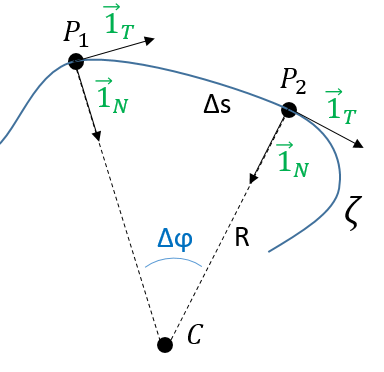

Sympathetic (red dashed) and parasympathetic (blue) nervous system innervate the gastrointestinal tract. Both carry sensory stimuli, though it appears that spinal afferent nerves in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord process pain.

In normal conditions the sympathetic nervous system is active during the stress ( fight and flight and fright system) and the parasympathetic is more active during the rest ( rest and digest system).

Sympathetic activation produces:

1) Increased heart rate and cardiac muscle contractility and bronchodilation of the lungs.

2) Constriction of blood vessels in many parts of the body, especially in the bowels and vasodilation of the muscle vessels.

3) Inhibition of stomach and intestinal action to the point where digestion slows down or stops, the same is for defecation and urination.

4) General effect on the sphincters of the body.

5) Paling or flushing, or alternating between both.

6) Liberation of nutrients (particularly fat and glucose) for muscular action.

7) Inhibition of the lacrimal gland (responsible for tear production) and salivation.

8) Dilation of pupil (mydriasis).

9) Relaxation of bladder.

10) Inhibition of erection.

11) Auditory exclusion (loss of hearing).

12) Tunnel vision (loss of peripheral vision).

13) Disinhibition of spinal reflexes; and shaking

14) Increased glucose production and mobilization by the liver

15) Increased lipolysis within fat tissue.

Parasympathetic activation produces:

1) In the stomach and intestines, parasympathetic stimulation leads to increased motility and relaxation of sphincters and increased gastric secretions to aid in digestion.

2) Parasympathetic stimulation leads to vasodilation of internal blood vessels, especially intestinal vasculature.

3) In the gallbladder, parasympathetic stimulation induces contraction to release bile.

4) In the pancreas, parasympathetic stimulation leads to the release of digestive enzymes and insulin

5) In salivary glands, parasympathetic stimulation leads to high volume secretion of potassium ions, water, and amylase

6) In the heart, parasympathetic stimulation, causes decreased heart rate and velocity of conduction through the AV node.

7) In the eye, parasympathetic stimulation, causes contraction of the sphincter muscle of the iris, leading to constriction of the pupil (miosis). Additionally, it causes contraction of the ciliary muscle, improving near vision.

8) In the lungs, parasympathetic stimulation of M3 receptors leads to bronchoconstriction. It also increases bronchial secretions.

9) In the kidneys and bladder, parasympathetic stimulation, stimulates peristalsis of ureters, contraction of the detrusor muscle, and relaxation of the internal urethral sphincter aiding in the flow and excretion of urine.

10) Smooth muscle relaxation in the helicine arteries of the penis, allowing blood to fill the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum, causing an erection. The PNS also gives excitatory signals to the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate.

Current research on the topic suggests a biopsychosocial model of the disorder, implicating physiological, emotional, behavioral and cognitive factors. Approximately 40–60% of patients with IBS who seek medical care also report psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, or somatization. Interestingly, however, psychiatric symptoms in patients with IBS in the general population are not as prevalent. It is thought that these psychiatric disturbances influence coping skills and illness-associated behaviors. A history of abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional) has been correlated with symptom severity. More than half of patients who are seen by a physician for Irritable Bowel Disease report stressful life events coinciding with or preceding the onset of symptoms. Stress is known to alter gastrointestinal function. Patients who suffer from IBS have amplified colonic motility responses when compared to normal volunteers (those who do not have any symptoms of IBS).

We believe the limbic system (an area of the brain where stress is perceived and experienced and recorded) is critically involved. The majority of these recordings are not available in the conscious mind. In everyday life each event is processed between conscious mind and limbic system and the ultimate response is evaluated between past experiences and actual information received and then the final reaction is decided. If the limbic system is in stress mode or imbalanced mode all consecutive behaviour of autonomic nervous system will be abnormal.

Diagnosis :

In the absence of definitive diagnostic markers, the diagnosis of IBS rests on physician’s recognition of classic clinical symptoms and the exclusion of other diseases. To facilitate comparisons among different populations and assist in epidemiological studies of IBS, two sets of criteria for diagnosis have been developed—the Manning and Rome Criteria. A multinational working team subsequently developed the Rome Criteria. The original criteria, Rome 1, were recently revised and the new Rome 2 diagnostic criteria are included below.

Manning Criteria:

Abdominal pain that is relieved with a bowel movement.

Pain associated with more frequent stools.

Sensation of incomplete evacuation.

Passage of mucous.

Abdominal distension.

Rome Criteria

Continuous or recurrent symptoms

of:

Abdominal pain, relieved with defecation, or associated with change in frequency or consistency of stool

and/or

Disturbed defecation( two or more of):

Altered stool frequency

Altered stool form (hard or loose/watery)

Altered stool passage (straining or urgency, feeling of incomplete evacuation)

Passage of mucus

usually with bloating or feeling of abdominal distension

Revised Rome Criteria (65)

At least 12 weeks or more, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months of abdominal disconfort or pain that has two out of three features:

-Relieved with defecation

and/or

-Onset associated with a change in frequency of

and/or

-onset associated with a change in form(appearance) of stool

Symptoms that cumulatively support the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome

-Abnormal stool frequency(for reasurches puposes “abnormal” may be defined as greater than 3 bowel movements per day and less than three bowel movements per week

– Abnormal stool form

lumpy/hard or loose/waterystool)

-Abnormal stool passage( straining, urgency, or feeling of incomplete evacuation)

-Passage of mucus

-Bloating or feeling of abdominal distension

Diagnostic Approach

Effective diagnosis of IBS begins with a careful history and physical examination. The initial evaluation should also include: a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate as well as a careful study of food allergies and a stool test for fecal occult blood . A colonoscopy should be performed in patients to exclude other types of bowel diseases. Once a diagnosis of IBS has been made, attention should be shifted to treatment. Continued investigations due to persistent symptoms are not warranted and may ultimately undermine a patient’s confidence in both the disorder diagnosis and the attending physician.

Therapy Overview

Management of patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome is based on a positive diagnosis of the syndrome, exclusion of organic disorders, and specific therapies. Treatment for IBS should address the three main pathophysiologically important factors : psychosocial disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, and dysmotility. Treatment should be patient oriented and geared towards symptom–specific relief. The majority of conventional IBS treatments currently used is empiric and has not been formally reviewed and scientifically approuved. Therapies may include fiber consumption for constipation, anti-diarrheals, smooth muscle relaxants for pain, and psychotropic agents for pain, diarrhea and depression. Patients with mild or infrequent symptoms may benefit from the establishment of a physician-patient relationship, patient education and reassurance, dietary modification, and simple measures such as fiber consumption. Patients with constipation-predominant IBS can generally be treated with osmotic mild laxatives. Stronger laxatives should be reserved for patients who do not respond to fiber consumption and gentle osmotic laxatives.

Physician-Patient Relationship :

:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), is classified as a functional gastrointestinal disease. Autonomic nervous system remodeling by limbic rehabilitation is a very sophisticated technique allowing a physiological treatment of bowel diseases . In cases of “pure irritable bowel syndrome” the efficiency of the treatment is now confirmed (hundreds of patients successfully treated) it’s also the same in IBS associated with nonspecific colitis. Now we begin to try successfully the IBD patients. To understand the efficacy of this technic we must begin to study the etiology and the exact mechanism leading to these abnormalities. IBS, is a chronic condition of the lower gastrointestinal tract that affects as many as 15% of adults in the world. Not easily characterized by structural abnormalities, infection, or metabolic disturbances, the underlying mechanisms of IBS remained for many years unclear.Recent research, however, has lead to an increased understanding of IBS. As a result, IBS is often referred to as spastic, nervous or irritable colon. Its hallmark is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with a change in the consistency and/or frequency of bowel movements.

The frequency of IBS in any given population depends, in part, on the ethnic and cultural background of the population being studied, and the criteria used to diagnose the disease. Eight to 20% of adults in the Western world report symptoms consistent with IBS (approximately 65% of these are women). Asia and Africa have similar rates to those in the Western world in general. In India IBS is more common among men, although it is possible that this is a result of differences in symptom reporting and health care use between genders.

The symptoms of IBS may include abdominal pain, distention, bloating, indigestion and various symptoms of defecation. There are three subcategories of IBS, according to the principal symptoms. These are pain associated with diarrhea; pain associated with constipation; and pain and diarrhea alternating with constipation. IBS is not a psychiatric disorder, although it is tied to emotional and social stress, which can affect both the onset and severity of symptoms. IBS patients suffer from a disproportionately higher rate of co-morbidity with other disorders, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, pelvic pain and psychiatric disorders. The primary features of the syndrome include motility, sensation and central nervous system dysfunction. Motility dysfunction may be manifest in muscle spasms; contractions can be very slow or fast. An increased sensitivity to stimuli causes pain and abdominal discomfort. Researchers also suspect that the regulatory conduit between the central and enteric pathway in patients suffering from IBS may be impaired. Research suggests that many patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome have disorganized and appreciably more intense colonic contractions than normal controls.

Pathophysiology :

Enteric propulsion and sensation are, in part, mediated by acetylcholine and serotonin (5HT). The physiology of sensation in the gut is multifaceted. Entero-endocrine cells transmit mechanical and chemical messages. The communication between gut and brain results in reflex responses mediated at three levels—prevertebral ganglia, spinal cord and brainstem. 5-HT, substance P, CGRP, norepinephrine, kappa opiate and nitric oxide are all involved in the perception and autonomic response to visceral stimulation. Sensation is conveyed from the viscus to the conscious perception via neurons in vagal and parasympathetic fibers. Afferent nerves in the dorsal root ganglion synapse with neurons in the dorsal horn. These signals result in reflexes that control motor and secretory functions as they synapse with efferent paths in the prevertebral ganglia and spinal cord. Pain is processed through spinal afferents in the dorsal horn. Ultimately, stimulation of the brainstem brings sensation to a conscious level :

Bidirectional signaling between the brainstem and the dorsal horn mediate sensation. The descending pathways are primarily adrenergic and serotonergic and affect incoming stimuli. End organ sensitivity, stimulus intensity changes or receptive field size of the dorsal horn neuron and limbic system modulation are the mechanisms involved in visceral hypersensitivity. Enteric inflammatory cells may also play an important role in the pathophysiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinicians have for many years recognized that the onset of IBS often follows an episode of acute gastroenteritis. Inflammation may alter intestinal cytokine milieu and motility, both of which can result in an increase in a patient’s pain sensation. The menstrual cycle may also affect gut sensation and motility. Other factors, such as malabsorption of sugars (lactose, fructose, and sorbitol), probably aggravate underlying IBS, rather than serving as root causes of the disorder. In patients with rapid transit times, short or medium chain fatty acids can reach the right colon and cause diarrhea.

Symptoms:

The hallmark of IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with either a change in bowel habits or disordered defecation. The pain or discomfort associated with IBS is often poorly localized and may be migratory and variable. It may occur after a meal, during stress or at the time of menses. In addition to pain and discomfort, altered bowel habits are common, including diarrhea, constipation, and diarrhea alternating with constipation. Patients also complain of bloating or abdominal distension, mucous in the stool, urgency, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation. Some patients describe frequent episodes, whereas others describe long symptom-free periods. Patients with irritable bowel frequently report symptoms of other functional gastrointestinal disorders as well, including chest pain, heartburn, nausea or dyspepsia, difficulty swallowing, or a sensation of a lump in the throat or closing of the throat. Patients with IBS are generally classified according to the type of bowel habits that accompany pain. Some patients have diarrhea-predominant symptomatology, others constipation-predominant, and still others have a combination of the two. Some patients alternate between different subgroups. Symptoms may vary from barely noticeable to debilitating, at times within the same patient. In some patients, stress or life crises may be associated with the onset of symptoms, which may then disappear when the stress dissipates. Other patients seem to have random IBS episodes with spontaneous remissions. Still others describe long periods of symptoms and long symptom-free periods. In general, the symptoms of IBS wax and wane throughout life, but the majority of patients seen by physicians is 20–50 years old. In approximately 50% of patients, symptoms begin before age 35. The disorder is also recognized in children, generally appearing in early adolescence. Many patients can trace the onset of symptoms back to childhood. The prevalence of IBS is slightly lower in the elderly, and in this patient population organic disorders must be excluded. Extraintestinal symptoms are common in patients with IBS. These may include headache, sleep disturbances, post-traumatic stress disorder, temporomandibular joint disorder, sicca syndrome, back/pelvic pain, myalgias, back pain, and chronic pelvic pain. Fibromyalgia and interstitial cystitis are also frequently encountered in patients with IBS. In fact, Fibromyalgia occurs in up to 33% of patients with IBS and almost half of patients with fibromyalgia also have IBS.

The autonomic nervous systems and the bowel:

Sympathetic (red dashed) and parasympathetic (blue) nervous system innervate the gastrointestinal tract. Both carry sensory stimuli, though it appears that spinal afferent nerves in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord process pain.

In normal conditions the sympathetic nervous system is active during the stress ( fight and flight and fright system) and the parasympathetic is more active during the rest ( rest and digest system).

Sympathetic activation produces:

1) Increased heart rate and cardiac muscle contractility and bronchodilation of the lungs.

2) Constriction of blood vessels in many parts of the body, especially in the bowels and vasodilation of the muscle vessels.

3) Inhibition of stomach and intestinal action to the point where digestion slows down or stops, the same is for defecation and urination.

4) General effect on the sphincters of the body.

5) Paling or flushing, or alternating between both.

6) Liberation of nutrients (particularly fat and glucose) for muscular action.

7) Inhibition of the lacrimal gland (responsible for tear production) and salivation.

8) Dilation of pupil (mydriasis).

9) Relaxation of bladder.

10) Inhibition of erection.

11) Auditory exclusion (loss of hearing).

12) Tunnel vision (loss of peripheral vision).

13) Disinhibition of spinal reflexes; and shaking

14) Increased glucose production and mobilization by the liver

15) Increased lipolysis within fat tissue.

Parasympathetic activation produces:

1) In the stomach and intestines, parasympathetic stimulation leads to increased motility and relaxation of sphincters and increased gastric secretions to aid in digestion.

2) Parasympathetic stimulation leads to vasodilation of internal blood vessels, especially intestinal vasculature.

3) In the gallbladder, parasympathetic stimulation induces contraction to release bile.

4) In the pancreas, parasympathetic stimulation leads to the release of digestive enzymes and insulin

5) In salivary glands, parasympathetic stimulation leads to high volume secretion of potassium ions, water, and amylase

6) In the heart, parasympathetic stimulation, causes decreased heart rate and velocity of conduction through the AV node.

7) In the eye, parasympathetic stimulation, causes contraction of the sphincter muscle of the iris, leading to constriction of the pupil (miosis). Additionally, it causes contraction of the ciliary muscle, improving near vision.

8) In the lungs, parasympathetic stimulation of M3 receptors leads to bronchoconstriction. It also increases bronchial secretions.

9) In the kidneys and bladder, parasympathetic stimulation, stimulates peristalsis of ureters, contraction of the detrusor muscle, and relaxation of the internal urethral sphincter aiding in the flow and excretion of urine.

10) Smooth muscle relaxation in the helicine arteries of the penis, allowing blood to fill the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum, causing an erection. The PNS also gives excitatory signals to the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate.

Current research on the topic suggests a biopsychosocial model of the disorder, implicating physiological, emotional, behavioral and cognitive factors. Approximately 40–60% of patients with IBS who seek medical care also report psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, or somatization. Interestingly, however, psychiatric symptoms in patients with IBS in the general population are not as prevalent. It is thought that these psychiatric disturbances influence coping skills and illness-associated behaviors. A history of abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional) has been correlated with symptom severity. More than half of patients who are seen by a physician for Irritable Bowel Disease report stressful life events coinciding with or preceding the onset of symptoms. Stress is known to alter gastrointestinal function. Patients who suffer from IBS have amplified colonic motility responses when compared to normal volunteers (those who do not have any symptoms of IBS).

We believe the limbic system (an area of the brain where stress is perceived and experienced and recorded) is critically involved. The majority of these recordings are not available in the conscious mind. In everyday life each event is processed between conscious mind and limbic system and the ultimate response is evaluated between past experiences and actual information received and then the final reaction is decided. If the limbic system is in stress mode or imbalanced mode all consecutive behaviour of autonomic nervous system will be abnormal.

Diagnosis :

In the absence of definitive diagnostic markers, the diagnosis of IBS rests on physician’s recognition of classic clinical symptoms and the exclusion of other diseases. To facilitate comparisons among different populations and assist in epidemiological studies of IBS, two sets of criteria for diagnosis have been developed—the Manning and Rome Criteria. A multinational working team subsequently developed the Rome Criteria. The original criteria, Rome 1, were recently revised and the new Rome 2 diagnostic criteria are included below.

Manning Criteria:

Abdominal pain that is relieved with a bowel movement.

Pain associated with more frequent stools.

Sensation of incomplete evacuation.

Passage of mucous.

Abdominal distension.

Rome Criteria

Continuous or recurrent symptoms

of:

Abdominal pain, relieved with defecation, or associated with change in frequency or consistency of stool

and/or

Disturbed defecation( two or more of):

Altered stool frequency

Altered stool form (hard or loose/watery)

Altered stool passage (straining or urgency, feeling of incomplete evacuation)

Passage of mucus

usually with bloating or feeling of abdominal distension

Revised Rome Criteria (65)

At least 12 weeks or more, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months of abdominal disconfort or pain that has two out of three features:

-Relieved with defecation

and/or

-Onset associated with a change in frequency of

and/or

-onset associated with a change in form(appearance) of stool

Symptoms that cumulatively support the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome

-Abnormal stool frequency(for reasurches puposes “abnormal” may be defined as greater than 3 bowel movements per day and less than three bowel movements per week

– Abnormal stool form

lumpy/hard or loose/waterystool)

-Abnormal stool passage( straining, urgency, or feeling of incomplete evacuation)

-Passage of mucus

-Bloating or feeling of abdominal distension

Diagnostic Approach

Effective diagnosis of IBS begins with a careful history and physical examination. The initial evaluation should also include: a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate as well as a careful study of food allergies and a stool test for fecal occult blood . A colonoscopy should be performed in patients to exclude other types of bowel diseases. Once a diagnosis of IBS has been made, attention should be shifted to treatment. Continued investigations due to persistent symptoms are not warranted and may ultimately undermine a patient’s confidence in both the disorder diagnosis and the attending physician.

Therapy Overview

Management of patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome is based on a positive diagnosis of the syndrome, exclusion of organic disorders, and specific therapies. Treatment for IBS should address the three main pathophysiologically important factors : psychosocial disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, and dysmotility. Treatment should be patient oriented and geared towards symptom–specific relief. The majority of conventional IBS treatments currently used is empiric and has not been formally reviewed and scientifically approuved. Therapies may include fiber consumption for constipation, anti-diarrheals, smooth muscle relaxants for pain, and psychotropic agents for pain, diarrhea and depression. Patients with mild or infrequent symptoms may benefit from the establishment of a physician-patient relationship, patient education and reassurance, dietary modification, and simple measures such as fiber consumption. Patients with constipation-predominant IBS can generally be treated with osmotic mild laxatives. Stronger laxatives should be reserved for patients who do not respond to fiber consumption and gentle osmotic laxatives.

Physician-Patient Relationship :

New treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases by autonomic nervous system remodeling

Epidemiology

- Higher incidence (9 – 20/100,000 person years) and prevalence (156 – 291/100,000 people) in populations of North American and Northern European descent (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Incidence increased in industrialized countries and urban versus rural locations, suggestive of environmental triggers, such as improved sanitation, reduced exposure to childhood enteric infections and mucosal immune system maturation (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Bimodal age distribution with peaks at 15 – 30 years and 50 – 70 years (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Family history of inflammatory bowel disease, particularly that of a first degree relative (5.7 – 15.5%) and Ashkenazi Jewish descent (3 – 5x) show higher risk of disease development (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Gastrointestinal infections with Salmonella spp, Shigella spp and Campylobacter spp have twice the risk of developing ulcerative colitis postinfection (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- M = F

- Former cigarette smoking is strong risk factor (Lancet 2017;389:1756)

- Almost always involves the rectum

- Continuous pattern of involvement proximally to include up to the entire colon (pancolitis)

- Rectal sparing can be seen, particularly after treatment (Lancet 2012;380:1606, Histopathology 2014;64:317, Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:94)

- Patch of inflammation in the cecum, often involving the periappendiceal mucosa (cecal patch), can be present (Lancet 2012;380:1606, Histopathology 2014;64:317)

- Approximately 20% of patients will have inflammation in the terminal ileum (backwash ileitis)

- Typically present in patients with pancolitis (Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1472)

- Focally enhanced gastritis can be seen in approximately 20% of pediatric patients (Pathology 2017;49:808)

- Extraintestinal manifestations:

- Peripheral arthritis, seronegative

- Ankylosing spondylitis or sacroiliitis

- Erythema nodosum

- Pyoderma granulosum

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

- Not fully known but appears to be a complex multifactorial process involving an overwhelming T helper type 2-like immune response, leading to mucosal injury in response to gut microbial dysbiosis in genetically predisposed patients

- Proposed mechanisms include:

- Damage to the colonic epithelial barrier due to dysregulation of epithelial tight junctions, which provide a physical barrier between the immune cells and the luminal microbes, leads to increased permeability (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Colonic epithelium upregulation of antimicrobial peptides, known as beta defensins (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Disruption in the homeostatic balance of the mucosal immunity and the enteric nonpathogenic bacteria, resulting in the patient’s aberrant immune response to the enteric commensal bacteria (Lancet 2012;380:1606, Front Microbiol 2018;9:2247)

- Increased number of colonic epithelium activated and mature dendritic cells with increased stimulatory capacity (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Increased expression of TLR4 by lamina propria cells and TLR4 polymorphism, which can alter susceptibility to enteric infections and tolerance to commensal bacteria (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Disruption in the homeostatic balance between regulatory and effector T cells, leading to a nonclassic natural killer T cell production of IL5 and IL13, which have cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells, mediating an atypical Th2 response

- IL13 can induce a positive feedback system on the natural killer T cells, leading to increased tissue injury (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Increase in proinflammatory cytokines, chemoattractants such as CXCL8 and adhesion molecules such as MadCAM1 recruit increased leukocytes to the colonic mucosa (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Other genetic risk loci include IL23 and IL10, JAK2 kinase pathway genes, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α, CDH1 and laminin β1 (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

Imagine the situation of this gazelle:

- Clinical symptoms include bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, mucus discharge, fecal urgency, tenesmus; in severe cases, symptoms may include weight loss, fever or colonic perforation (Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:1357)

- Characterized by alternating periods of clinical relapse and remission

- At diagnosis, most patients have mild to moderate symptoms, with fewer than 10% having severe disease

- Patients presenting with severe disease are usually those diagnosed at young ages (15 – 30 years of age) or with simultaneous PSC (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- 30 – 50% of patients will present with disease of the rectum or sigmoid colon and only approximately 20% of patients will present with pancolitis (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Appendectomy due to acute appendicitis before age 20 has been shown to be protective against ulcerative colitis (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Fulminant colitis, known as acute, clinically severe colitis involving the entire colon and requiring surgical resection, can be seen (Histopathology 2014;64:317)

- Toxic megacolon (marked colonic dilation with signs of systemic toxicity) can occur and requires surgical intervention (BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2018227121)

- May have iron deficiency anemia

- Increased risk of hypercoagulability and thrombosis

- Disease severity via endoscopy is stratified as remission, mild, moderate or severe

- Numerous severity indices exist

- Goal of endoscopic remission following therapy

- Correlation of clinical symptoms with endoscopic and histological examination

- Exclusion of other etiologies for colitis (infection, drug, etc.)

- Colonoscopy with biopsy is essential

- Endoscopic findings include erythema, loss of vascular pattern, granularity, friability and erosion / ulceration

- Often a sharp demarcation between inflammation and normal mucosa (Lancet 2017;389:1756)

- High definition colonoscopy or chromoendoscopy are preferred over traditional white light endoscopy due to higher sensitivity (93 – 97%) and specificity (93%) (Dig Endosc 2016;28:266, Histopathology 2015;66:37)

- Targeted biopsies of mucosal abnormalities and random biopsies at each segment of the colon help determine microscopic extent of disease (Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017;13:357, Dig Endosc 2016;28:266)

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy to rule out upper gastrointestinal tract involvement

- Overall nonspecific

- Markers of inflammation

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥ 30 mm/h

- C reactive protein > 8 mg/L

- Leukocytosis and thrombocytosis

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- Fecal calprotectin > 50.0 mcg/g

- References: Pathologica 2021;113:39, Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:207

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) may be useful in identifying bowel wall thickening and ahaustral colon but are not sensitive or specific for diagnosis of acute disease

- Plain upright abdominal Xray can be performed in patients with severe colitis to assess for toxic megacolon

- Mid transverse colon dilation > 5.5 cm (Lancet 2017;389:1756)

- Target or double halo sign can be seen in cases of advanced disease

- Colorectal carcinoma is the cause of death in an estimated 15% of inflammatory bowel disease patients; risk factors for developing colorectal carcinoma include:

- Duration of disease (increased risk of up to 2% after 10 years, 8% after 20 years and 18% after 30 years)

- Extent of disease, with pancolitis carrying the highest risk

- Simultaneous PSC, severity of colitis, psuedopolyps, family history of sporadic colorectal carcinoma and male sex

- Risk factors for aggressive or complicated disease include:

- Young age at onset, pancolitis, lack of endoscopic healing, deep ulcerations and high concentrations of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- References: Lancet 2012;380:1606, Lancet 2017;389:1756

Treatment

(All treatment with drugs is only symptomatic because they treat the inflammation and not the cause and origin of the disease and the only way to cure the disease is limbic rehabilitation and autonomic nervous system remodeling.)

- 5-aminosalicylate agents are first line therapy for mild to moderate disease

- Corticosteroids

- Patients with moderate to severe disease may require thiopurines or biologic agents (anti-TNF therapy or anti-integrin therapy) (Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:1357)

- Patients with proctitis only may be treated with topical agents

- Colorectal carcinoma surveillance at 8 – 10 years after the onset of symptoms and fixed interval surveillance every 1 – 2 years afterward (Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017;13:357)

- Surgery will eventually be required in 20 – 30% of patients with ulcerative colitis that has become refractory to medical management or who have developed dysplasia or colorectal carcinoma (Lancet 2012;380:1606)

- Total colectomy with ileal pouch – anal anastomosis is preferred surgical intervention

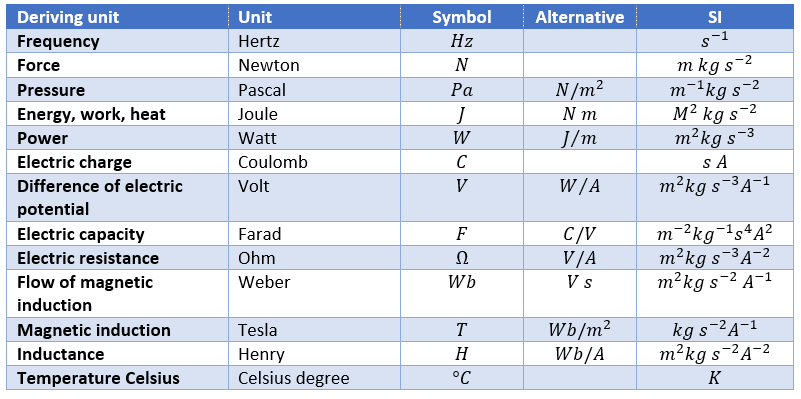

High blood pressure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality due to its association with coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and kidney disease. The extent of damage to the target organs (i.e., heart, brain and kidneys) determines the prognosis. According to W.H.O, 15 million people have a stroke each year and 5 million die and 5 million suffer from permanent disabilities. C.V.A ( cerebro-vascular accident) is rare in people under 40 and if it occurs, it is mainly due to hypertension. Hypertension and smoking are the two main modifiable risk factors. Four out of ten people who died from a stroke could have been saved if their blood pressure had been controlled. Recent guidelines clearly indicate that the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension is as important as that of systolo-diastolic hypertension.

The different levels of blood pressure according to WHO:

High: Ts:> or = 140 mm Hg and Td:> or = 90 mmHg

at risk (prehypertension): Ts: 120-139 mm Hg and Td: 80-89 mm Hg

Normal: Ts <120 mm Hg and Td: <80 to 80 mm Hg

Blood pressure is determined by 3 basic elements:

Left ventricular ejection volume, Heart rate and peripheral vascular resistance

PA = VES x frc x RVP

This is equal to cardiac output x peripheral vascular resistance.

The role of the sympathetic nervous system in high blood pressure :

In 1988: Vargas HM, Brezenoff HE. Suppression of hypertension during chronic reduction of cerebral acetylcholine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension. 1988; 6 (9): 739–745.

Experiments were conducted to determine the effects of chronic depletion of brain acetylcholine (ACh) on the development and maintenance of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). Synthesis of brain ACh was inhibited by chronic infusion of hemicholinium-3 (HC-3) into the cerebral ventricles, and systolic blood pressure was monitored by tail cuff occlusion. In 5-week-old SHR, infusion of HC-3 (0.25 micrograms/h) suppressed development of hypertension when compared to saline-infused control SHR during the 21 days of infusion (140 versus 190 mmHg on day 21). Hypothalamic and brain-stem ACh during this period was reduced by 50% and by 60-75%, respectively. In 18-week-old SHR with established hypertension, HC-3 (0.25 and 0.5 micrograms/h) reduced systolic blood pressure by 35-40 mmHg for 8 days, after which pressures returned to control hypertensive levels (191 mmHg) by day 14. The increase in blood pressure was accompanied by recovery of hypothalamic ACh levels to 75% of control. The specificity and physiological effectiveness of HC-3 was shown by its ability to inhibit the centrally mediated pressor response to physostigmine but not to oxotremorine. Infusion of HC-3 did not affect body growth, water consumption, body temperature or gross behavior. From this study, it can be concluded that brain cholinergic neurons are an important component in the development and the maintenance of hypertension in the SHR.

In 1991: Julius S. Deregulation of the autonomic nervous system in human hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 1991; 67 (10): 3B – 7B

An increased sympathetic drive combined with decreased parasympathetic inhibition is found in patients with borderline hypertension, who characteristically have rapid heart rates, high cardiac output and relatively normal vascular resistance (hyperkinetic state). In established hypertension, cardiac output is normal, vascular resistance is elevated and signs of increased sympathetic drive are absent. Apparently hemodynamics and sympathetic drive change during hypertension. The mechanism of the hemodynamic transition in the course of hypertension is well understood. Cardiac output returns from elevated to normal values as beta-adrenergic receptors down-regulate and stroke volume decreases (due to decreased cardiac compliance). The high blood pressure induces vascular hypertrophy, which in turn leads to increased vascular resistance. The mechanism of the change of sympathetic tone from elevated in borderline hypertension to apparently normal in established hypertension can best be explained within the conceptual framework of the “blood-pressure-seeking” properties of the brain. In hypertension, the central nervous system seeks to maintain systemic blood pressure at the higher level. As hypertension advances and vascular hypertrophy develops, arterioles become hyperresponsive to vasoconstriction. At this point, less sympathetic drive is needed to maintain pressure-elevating vasoconstriction, and the central sympathetic drive is down-regulated. The etiology of increased sympathetic drive in hypertension remains unresolved. Subjects with increased sympathetic drive are also usually overweight and have elevated levels of insulin, cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as decreased high-density lipoproteins. Future research must focus on the link between coronary risk factors and sympathetic overactivity in hypertension.

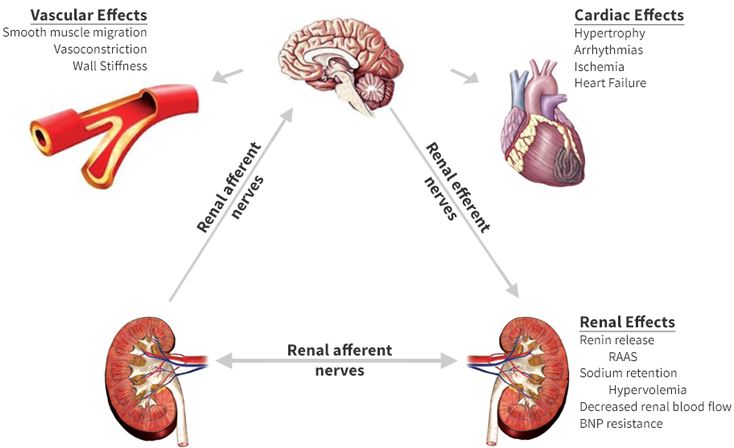

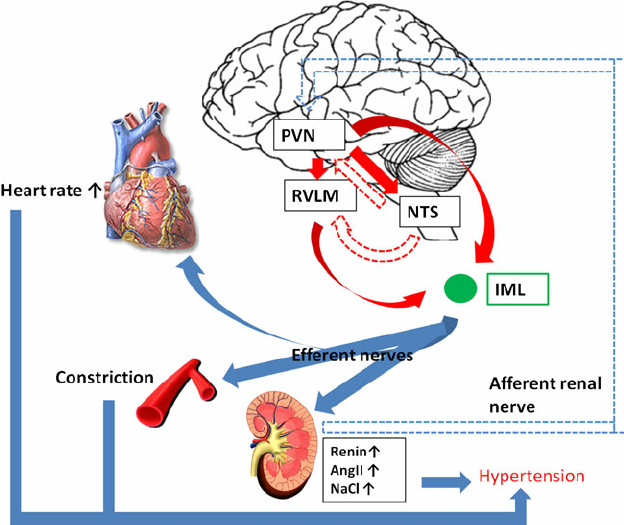

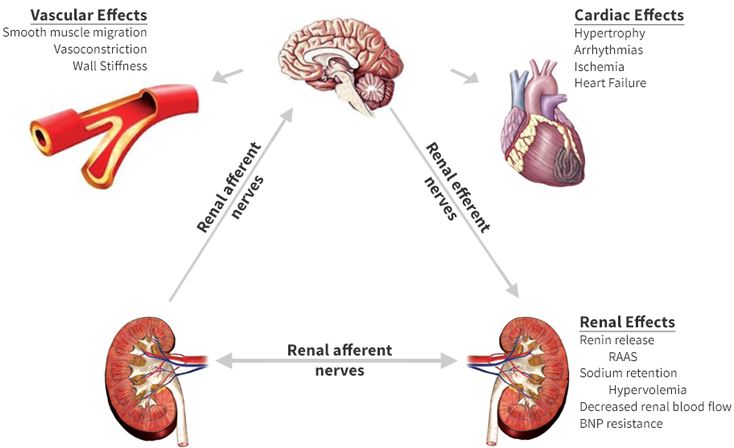

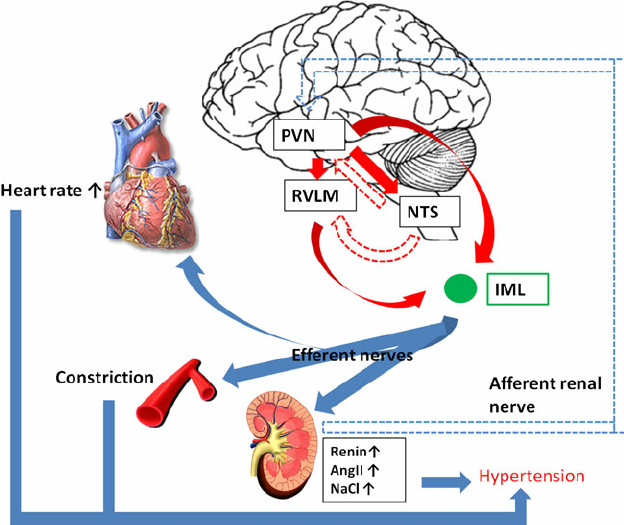

In 2012 Kumagai H & co : Importance of rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons in determining efferent sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure.

Accentuated sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) is a risk factor for cardiovascular events. In this review, we investigate our working hypothesis that potentiated activity of neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) is the primary cause of experimental and essential hypertension. Over the past decade, we have examined how RVLM neurons regulate peripheral SNA, how the sympathetic and renin-angiotensin systems are correlated and how the sympathetic system can be suppressed to prevent cardiovascular events in patients. Based on results of whole-cell patch-clamp studies, we report that angiotensin II (Ang II) potentiated the activity of RVLM neurons, a sympathetic nervous center, whereas Ang II receptor blocker (ARB) reduced RVLM activities. Our optical imaging demonstrated that a longitudinal rostrocaudal column, including the RVLM and the caudal end of ventrolateral medulla, acts as a sympathetic center. By organizing and analyzing these data, we hope to develop therapies for reducing SNA in our patients. Recently, 2-year depressor effects were obtained by a single procedure of renal nerve ablation in patients with essential hypertension. The ablation injured not only the efferent renal sympathetic nerves but also the afferent renal nerves and led to reduced activities of the hypothalamus, RVLM neurons and efferent systemic sympathetic nerves. These clinical results stress the importance of the RVLM neurons in blood pressure regulation. We expect renal nerve ablation to be an effective treatment for congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease, such as diabetic nephropathy.

In 2012 Kazushi Tsuda : Renin–Angiotensin System and Sympathetic Neurotransmitter Release in the Central Nervous System of Hypertension.

Many Studies suggest that changes in sympathetic nerve activity in the central nervous system might have a crucial role in blood pressure control. The present paper discusses evidence in support of the concept that the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) might be linked to sympathetic nerve activity in hypertension. The amount of neurotransmitter release from sympathetic nerve endings can be regulated by presynaptic receptors located on nerve terminals. It has been proposed that alterations in sympathetic nervous activity in the central nervous system of hypertension might be partially due to abnormalities in presynaptic modulation of neurotransmitter release. Recent evidence indicates that all components of the RAS have been identified in the brain. It has been proposed that the brain RAS may actively participate in the modulation of neurotransmitter release and influence the central sympathetic outflow to the periphery. This paper summarizes the results of studies to evaluate the possible relationship between the brain RAS and sympathetic neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system of hypertension.

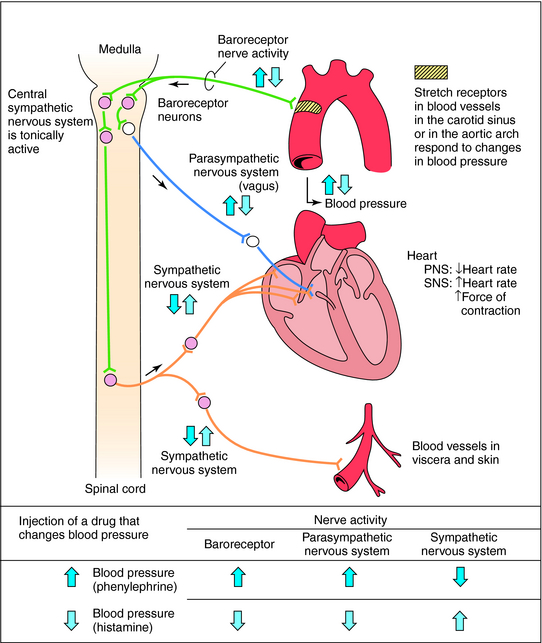

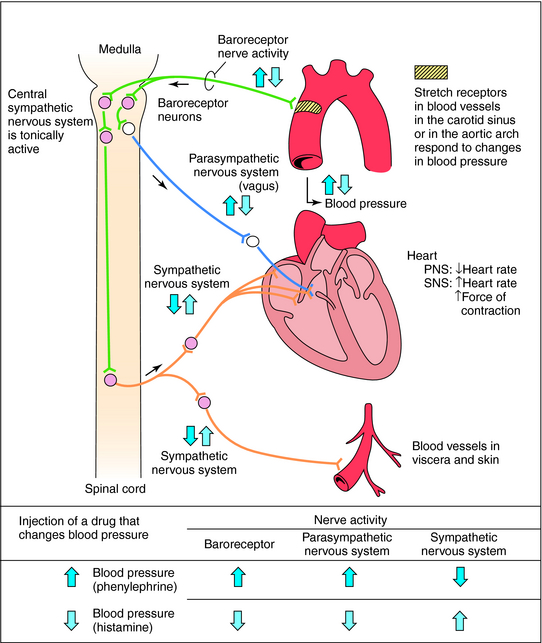

How the nervous system works ?

Acute control of baroreceptors: The vasomotor center includes the nucleus of the solitarius tract in the dorsal medulla (integration of baroreceptors), the rostral part of the ventral medulla (pressure region) and other centers in the pons and midbrain. Arterial baroreceptors respond to distension of the vascular wall by increasing the afferent impulse activity. This in turn decreases efferent sympathetic activity and increases vagal tone. The net effect is bradycardia and vasodilation.

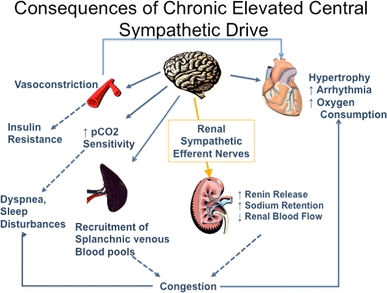

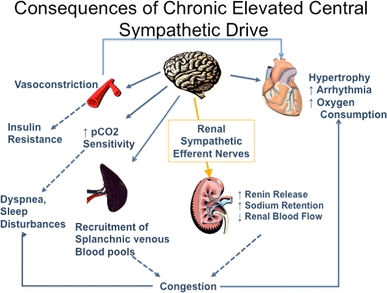

consequences of prolonged sympathetic hyperactivity :

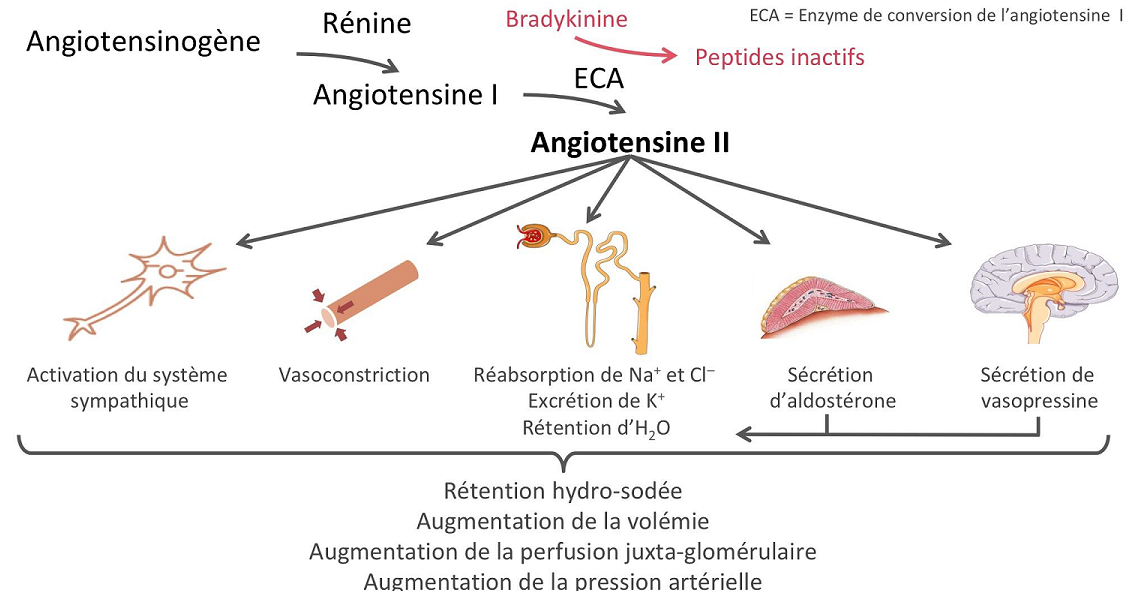

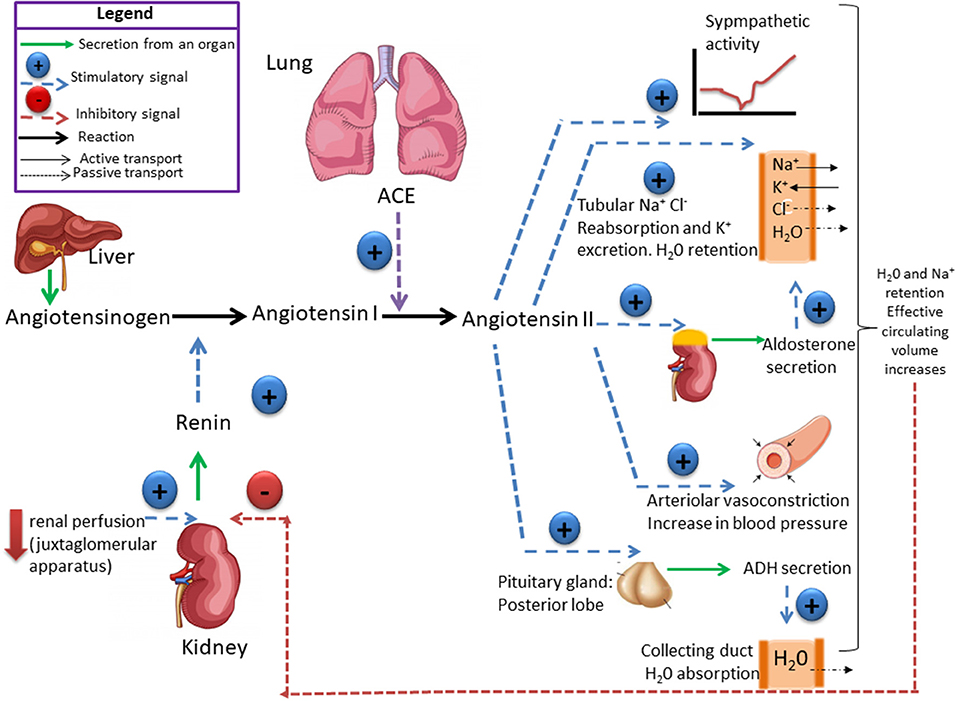

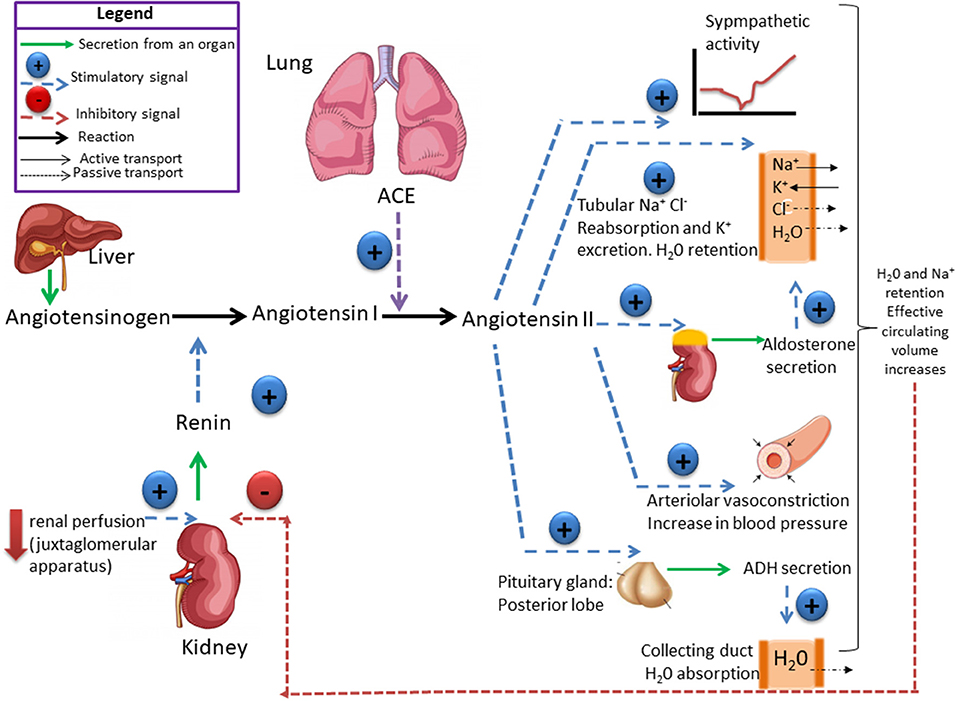

Renin-angiotensin system:

The renin protease cleaves angiotensin to give the inactive peptide angiotensin I. The latter is converted into an active octapeptide, angiotensin II by the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). Although the renin-angiotensin system is widespread in the body, the main source of renin is the juxtaglomerular apparatus of the kidney. This device detects the renal perfusion pressure and the sodium concentration in the distal tubular fluid. In addition, renin release is stimulated by adrenergic beta and decreased by alpha adrenergic stimulation. High concentrations of angiotensin II suppress renin secretion via a negative feedback loop. Angiotensin II acts on specific angiotensin receptors AT1 and AT2, causing a contraction of the smooth muscles and the release of aldosterone, prostacyclins and catecholamines. The renin – angiotensin – aldosterone system plays an important role in controlling blood pressure, including sodium balance.

In addition, renin release is stimulated by the sympathetic nervous system.

High concentrations of angiotensin II suppress renin secretion via a negative feedback loop. Angiotensin II acts on specific angiotensin receptors AT1 and AT2, causing a contraction of the smooth muscles and the release of aldosterone, prostacyclins and catecholamines. The renin – angiotensin – aldosterone system plays an important role in controlling blood pressure, including sodium balance.

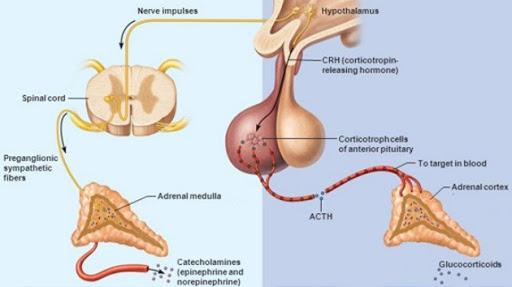

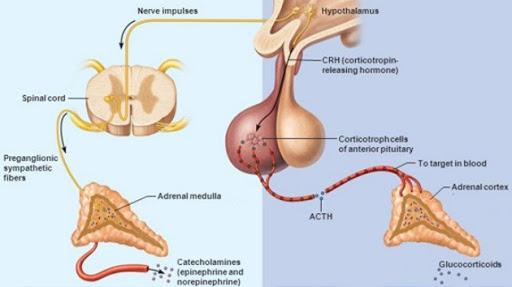

Adrenal steroids:

Mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids increase blood pressure. This effect is mediated by sodium and water retention (mineralocorticoids) or increased vascular reactivity (glucocorticoids). In addition, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids increase vascular tone by regulating receptors for pressive hormones such as angiotensin II. Renomedullary vasodepression The renomedullary interstitial cells, located mainly in the renal papilla, secrete an inactive substance medullipine I. This lipid is transformed in the liver into medullipine II. This substance exerts a prolonged hypotensive effect, possibly by direct vasodilation, inhibition of the sympathetic drive in response to hypotension and a diuretic action. It is assumed that the activity of the renomedullary system is controlled by the renal medullary blood flow. Sodium and water excretion Sodium and water retention is associated with an increase in blood pressure. It is postulated that sodium, via the sodium-calcium exchange mechanism, causes an increase in intracellular calcium in the vascular smooth muscle resulting in an increase in vascular tone. The main cause of sodium and water retention may be an abnormal relationship between sodium pressure and excretion resulting from decreased renal blood flow, reduced nephronic mass, and increased angiotensin or mineralocorticoids

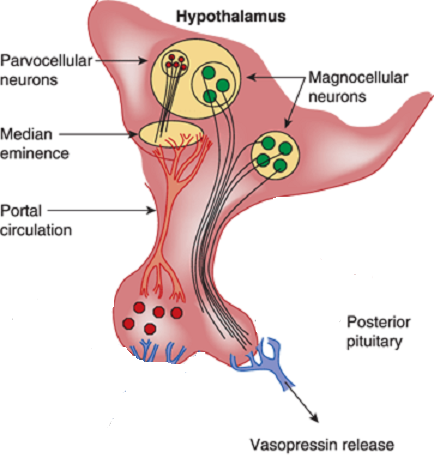

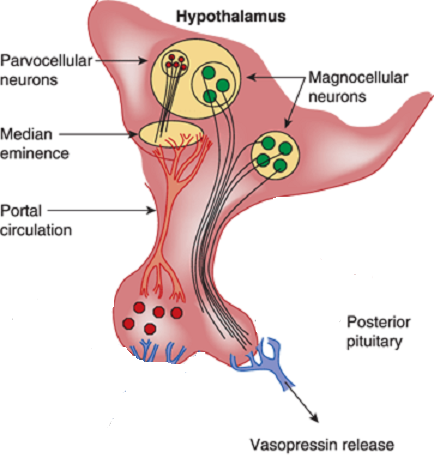

ADH ( vasopressin):

Vasopressin is a small hormone, synthesized in the hypothalamus and released into the circulation from the posterior lob of hypophysis. Although historically named as a result of its potent vasopressor actions, these actions only occur when plasma vasopressin is present in the plasma in supraphysiological concentrations. The most important action of vasopressin is its antidiuretic action on the collecting ducts of the kidney. This leads to a decrease in renal free water clearance, concentration of urine, and a reduction in urine volume. The net effect is the reabsorption of water into the blood, which, along with thirst-generated water intake, leads to normalization of plasma osmolality.Regulation of vasopressin secretion and action thus represents a key homeostatic process which protects the osmotic milieu of the body, allowing normal cellular function.

Synthesis :

Vasopressin is most abundantly produced in magnocellular neurosecretory neurons in the supraoptic and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei, transported to terminals in the neurohypophysis, and released into the general circulation. Vasopressin production is also found in parvocellular neurons in the PVN and vasopressinn produced in these neurons is transported to terminals in the external layer of the median eminence, from which it is released into the hypophysial portal system.

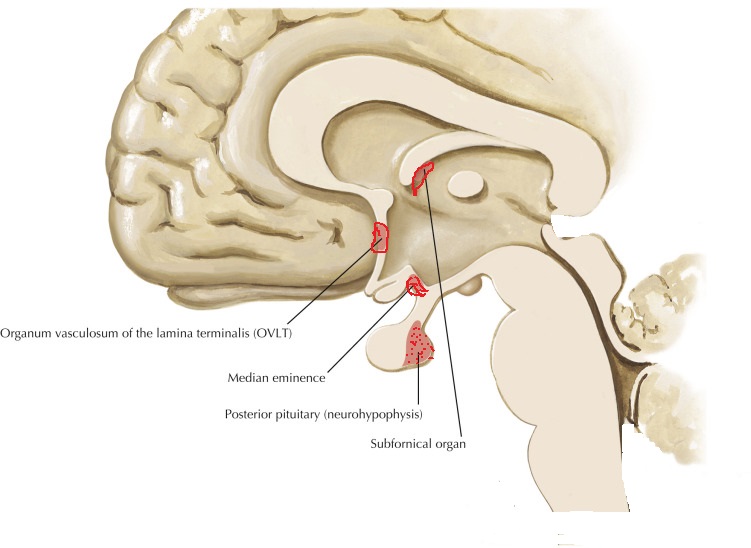

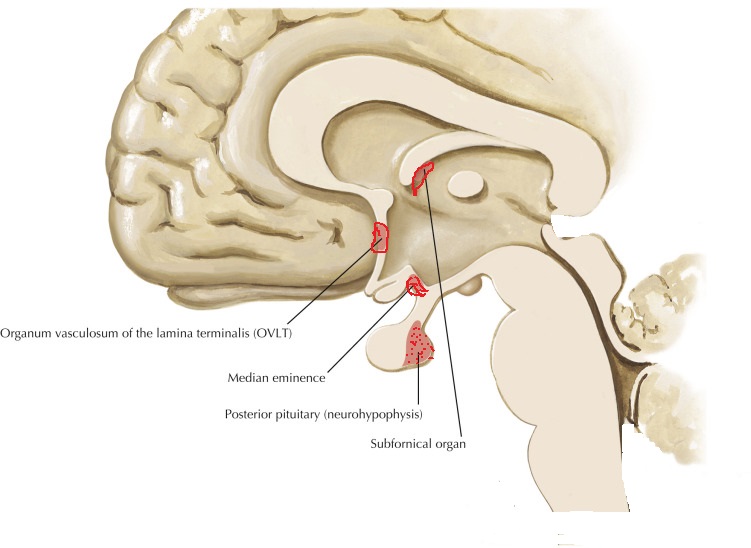

Release and feedback controle :

Vasopressin release is regulated by osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus (OVLT, SFO), which are exquisitely sensitive to changes in plasma osmolality of as little as 1% to 2%. Under hyperosmolar conditions, osmoreceptor stimulation leads to vasopressin release and stimulation of thirst. These two mechanisms result in increased water intake and retention. Vasopressin release is also regulated by baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, under conditions of hypovolemia, these receptors stimulate vasopressin release to increase plasma volume. At very high concentrations, vasopressin also causes vascular smooth muscle constriction through the V1 receptor, increasing vascular tone and therefore the blood pressure. Accordingly, vasopressin is often administered parenterally as a vasopressor agent in patients with hypotension that is refractory to volume restriction.

Vasopressin has effects on the immune system independent of its effect in stimulating the HPA axis. When given intraventricularly to rats, vasopressin decreases the T-cell response to mitogen independently of the HPA axis, probably via the sympathetic nervous system. Like CRH, vasopressin stimulates immune responses in peripheral tissues. Circulating or local vasopressin enhances lymphocyte reactions and potentiates primary antibody. Elevated vasopressin levels are found in a mouse model of autoimmune disease, and antibody neutralization ameliorates the inflammatory response in these mice. Vasopressin can potentiate the release of prolactin, a proinflammatory peptide hormone.

Vasopressin has effects on the immune system independent of its effect in stimulating the HPA axis. When given intraventricularly to rats, vasopressin decreases the T-cell response to mitogen independently of the HPA axis, probably via the sympathetic nervous system. Like CRH, vasopressin stimulates immune responses in peripheral tissues. Circulating or local vasopressin enhances lymphocyte reactions and potentiates primary antibody. Elevated vasopressin levels are found in a mouse model of autoimmune disease, and antibody neutralization ameliorates the inflammatory response in these mice. Vasopressin can potentiate the release of prolactin, a proinflammatory peptide hormone.

Because vasopressin has immunosuppressive effects when present in the central nervous system and immunosupportive effects when present in peripheral tissues, predicting which effect would predominate during vasopressin infusion in the ICU is difficult.

Vasopressin is a hormone of the posterior pituitary, that is secreted in response to high serum osmolarity. Excitation of atrial stretch receptors inhibits vasopressin secretion. Vasopressin is also released in response to stress, inflammatory signals, and some medications. Hypotension, morphine, nicotine, angiotensin II, glucocorticoids, and IL-6 all stimulate release of vasopressin. Circulating vasopressin levels are usually high in the early phase of septic shock, but vasopressin deficiency has been described in vasodilatory shock states in both adults and children. The level of vasopressin that is normal in the late phase of sepsis is unclear.

Vasopressin selectively raises free water reabsorption through the upregulation of aquaporin-2 water channels in the collecting duct, resulting in blood pressure elevation (Elliot et al., 1996; Linshaw 2011). Although it appears that the developing kidney is less sensitive to circulating vasopressin, plasma levels of vasopressin are markedly elevated in the neonate, especially after vaginal delivery, and its cardiovascular actions facilitate neonatal adaptation (Pohjavuori et al., 1985; Linshaw, 2011). The high vasopressin levels are in part also responsible for the diminished urine output of the healthy term neonate during the first day after birth. Under certain pathologic conditions, the dysregulated release of, or the end-organ unresponsiveness to, vasopressin significantly affects renal and cardiovascular functions and electrolyte and fluid status in the sick preterm and term neonate (Svenningsen et al., 1974). In the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), an uncontrolled release of vasopressin occurs in sick preterm and term neonates, with resulting water retention, hyponatremia, and oligouria. In the syndrome of diabetes insipidus, the lack of pituitary production of vasopressin or renal unresponsiveness to vasopressin results in polyuria and hypernatremia.

Le Peptide natriurétique auriculaire :

Le peptide natriurétique auriculaire (ANP) est libéré des granules auriculaires. Il produit une natriurèse, une diurèse et une baisse modeste de la pression artérielle, tout en diminuant la rénine et l’aldostérone plasmatiques. Les peptides natriurétiques modifient également la transmission synaptique des osmorécepteurs. Le (PNA) est libéré à la suite de la stimulation de l’oreillette par distension et étirement des récepteurs. Les concentrations de (PNA) sont augmentées par des pressions de remplissage élevées et chez les patients souffrant d’hypertension artérielle et d’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche comme la paroi du ventricule gauche est épaissie participe à la sécrétion d’ANP.

Eicosanoïdes :

Les métabolites de l’acide arachidonique modifient la pression artérielle par des effets directs sur le tonus musculaire lisse vasculaire et les interactions avec d’autres systèmes vasorégulateurs: système nerveux autonome, le système rénine-angiotensine – aldostérone et autres voies humorales. Chez les patients hypertendus, un dysfonctionnement des cellules endothéliales vasculaires pourrait entraîner une réduction des facteurs de relaxation dérivés de l’endothélium tels que l’oxyde nitrique, la prostacycline et le facteur hyperpolarisant dérivé de l’endothélium, ou une augmentation de la production de facteurs de contraction tels que l’endothéline-1 et le thromboxane A2. Systèmes kallikréine-kinine Les kallikréines tissulaires agissent sur le kininogène pour former des peptides vasoactifs. Le plus important est le bradykinin vasodilatateur. Les kinines jouent un rôle dans la régulation du débit sanguin rénal et de l’excrétion d’eau et de sodium. Les inhibiteurs de l’ECA diminuent la dégradation de la bradykinine en peptides inactifs. Mécanismes endothéliaux L’oxyde nitrique (NO) intervient dans la vasodilatation produite par l’acétylcholine, la bradykinine, le nitroprussiate de sodium et les nitrates. Chez les patients hypertendus, la relaxation dérivée de l’endothélium est inhibée. L’endothélium synthétise les endothélines, les vasoconstricteurs les plus puissants. La génération ou la sensibilité à l’endothéline-1 n’est pas plus élevée chez les sujets hypertendus que chez les sujets normotendus. Néanmoins, les effets vasculaires délétères de l’endothéline-1 endogène peuvent être accentués par une génération réduite d’oxyde nitrique causée par une dysfonction endothéliale hypertensive.

Stéroïdes surrénales :

Les minéraux et glucocorticoïdes augmentent la pression artérielle. Cet effet est médié par la rétention de sodium et d’eau (minéralocorticoïdes) ou une réactivité vasculaire accrue (glucocorticoïdes). De plus, les glucocorticoïdes et les minéralocorticoïdes augmentent le tonus vasculaire en régulant les récepteurs des hormones pressives telles que l’angiotensine II. Vasodépression rénomédullaire Les cellules interstitielles rénomédullaires, situées principalement dans la papille rénale, sécrètent une substance inactive la médullipine I. Ce lipide est transformé dans le foie en médullipine II. Cette substance exerce un effet hypotenseur prolongé, éventuellement par vasodilatation directe, inhibition de la pulsion sympathique en réponse à l’hypotension et une action diurétique. On suppose que l’activité du système rénomédullaire est contrôlée par le flux sanguin médullaire rénal. Excrétion de sodium et d’eau La rétention de sodium et d’eau est associée à une augmentation de la pression artérielle. Il est postulé que le sodium, via le mécanisme d’échange sodium-calcium, provoque une augmentation du calcium intracellulaire dans le muscle lisse vasculaire entraînant une augmentation du tonus vasculaire. La principale cause de rétention de sodium et d’eau peut être une relation anormale entre la pression et l’excrétion de sodium résultant d’une diminution du débit sanguin rénal, d’une masse néphronique réduite et d’une augmentation de l’angiotensine ou des minéralocorticoïdes. Physiopathologie L’hypertension est une élévation chronique de la pression artérielle qui, à long terme, cause des dommages aux organes terminaux et entraîne une augmentation de la morbidité et de la mortalité. La pression artérielle est le produit du débit cardiaque et de la résistance vasculaire systémique. Il s’ensuit que les patients souffrant d’hypertension artérielle peuvent avoir une augmentation du débit cardiaque, une augmentation de la résistance vasculaire systémique, ou les deux. Dans le groupe d’âge plus jeune, le débit cardiaque est souvent élevé, tandis que chez les patients plus âgés, une résistance vasculaire systémique accrue et une rigidité accrue du système vasculaire jouent un rôle dominant. Le tonus vasculaire peut être élevé en raison d’une stimulation accrue des récepteurs a-adrénergiques ou d’une libération accrue de peptides tels que l’angiotensine ou les endothélines. La dernière voie est une augmentation du calcium cytosolique dans le muscle lisse vasculaire provoquant une vasoconstriction. Plusieurs facteurs de croissance, dont l’angiotensine et les endothélines, provoquent une augmentation de la masse musculaire vasculaire lisse appelée remodelage vasculaire. A la fois une augmentation de la résistance vasculaire systémique et une augmentation de la résistance vasculaire

la rigidité augmente la charge imposée au ventricule gauche; cela induit une hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche et un dysfonctionnement diastolique ventriculaire gauche. Chez les jeunes, la pression du pouls générée par le ventricule gauche est

relativement faible et les ondes reflétées par le système vasculaire périphérique se produit principalement après la fin de la systole, augmentant ainsi la pression au début partie de la diastole et l’amélioration de la perfusion coronaire. Avec vieillissement, raidissement de l’aorte et des artères élastiques,augmente la pression du pouls. Les ondes réfléchies passent de la diastole précoce à la systole tardive. Il en résulte une augmentation de la postcharge ventriculaire gauche et contribue à l’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche. L’élargissement de la pression du pouls avec le vieillissement est un puissant prédicteur des maladies coronariennes. Le système nerveux autonome joue un rôle important dans le contrôle de la pression artérielle. Chez les patients hypertendus, une libération accrue et une sensibilité périphérique accrue à la noradrénaline peuvent être trouvées. De plus, il y a une réactivité accrue aux stimuli stressants. Une autre caractéristique de l’hypertension artérielle est la réinitialisation des baroréflexes diminution de la sensibilité des barorécepteurs. Le système rénine-angiotensine est impliqué au moins dans certaines formes d’hypertension (par exemple l’hypertension rénovasculaire) et est supprimé en présence d’hyperaldostéronisme primaire. Les patients âgés ou noirs ont tendance à souffrir d’hypertension à faible rénine. D’autres ont une hypertension à rénine élevée et ceux-ci sont plus susceptibles de développer un infarctus myocardique et d’autres complications cardiovasculaires. Dans l’hypertension essentielle humaine et expérimentale,l’hypertension, la régulation du volume et la relation entre la pression artérielle et l’excrétion de sodium (natriurèse sous pression) sont anormales. Des preuves considérables indiquent que la réinitialisation de la natriurèse sous pression joue un rôle clé dans la cause de l’hypertension. Chez les patients souffrant d’hypertension essentielle, la réinitialisation de la natriurèse sous pression se caractérise soit par un déplacement parallèle vers des pressions sanguines plus élevées et une hypertension insensible au sel, soit par une diminution de la pente de la natriurèse sous pression et de l’hypertension sensible au sel. Conséquences et complications de l’hypertension Les conséquences cardiaques de l’hypertension sont l’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche et la maladie coronarienne. L’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche est causée par une surcharge de pression et est concentrique. Il y a une augmentation de la masse musculaire et de l’épaisseur de la paroi mais pas du volume ventriculaire. L’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche altère la fonction diastolique, ralentit la relaxation ventriculaire et retarde le remplissage. L’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche est un facteur de risque indépendant de maladie cardiovasculaire, en particulier de mort subite. Les conséquences de l’hypertension sont fonction de sa gravité. Il n’y a pas de seuil de complications, car l’élévation de la pression artérielle est associée à une morbidité accrue dans toute la plage de pression artérielle (tableau 1).

La maladie coronarienne est associée à, et accélérée par, l’hypertension artérielle chronique, entraînant une ischémie myocardique et un infarctus du myocarde. En effet, l’ischémie myocardique est beaucoup plus fréquente chez les patients hypertendus non traités ou mal contrôlés que chez les patients normotendus. Deux principaux facteurs contribuent à l’ischémie myocardique: une augmentation de la demande en oxygène liée à la pression et une diminution de l’apport coronarien en oxygène résultant des lésions athéromateuses associées. L’hypertension est un facteur de risque important de décès par maladie coronarienne. L’insuffisance cardiaque est une conséquence d’une surcharge de pression chronique. Il peut commencer par un dysfonctionnement diastolique et évoluer vers une insuffisance systolique manifeste avec congestion cardiaque. Les AVC sont des complications majeures de l’hypertension; ils résultent d’une thrombose, d’une thrombo-embolie ou d’une hémorragie intracrânienne. La maladie rénale, initialement révélée par une micro albuminaémie, peut évoluer lentement et se manifester au cours des années suivantes. Traitement à long terme de l’hypertension Tous les antihypertenseurs doivent agir en diminuant le débit cardiaque, la résistance vasculaire périphérique ou les deux. Les classes de médicaments les plus couramment utilisées comprennent les diurétiques thiazidiques, les bbloquants, les inhibiteurs de l’ECA, les antagonistes des récepteurs de l’angiotensine II, les bloqueurs des canaux calciques, les bloqueurs des récepteurs adrénergiques, les bloqueurs combinés des a et b, les vasodilatateurs directs et certains médicaments à action centrale tels que les a2- agonistes des récepteurs adrénergiques et agonistes des récepteurs de l’imidazoline I1. La modification du style de vie est la première étape du traitement de l’hypertension; il comprend une restriction modérée en sodium, une réduction de poids chez les obèses, une diminution de la consommation d’alcool et une augmentation de l’exercice. Un traitement médicamenteux est nécessaire lorsque les mesures ci-dessus n’ont pas réussi ou lorsque l’hypertension est déjà à un stade dangereux (stade 3) lors de sa première reconnaissance.

Thérapie médicamenteuse

Diurétiques:

Le traitement diurétique à faible dose est efficace et réduit le risque d’accident vasculaire cérébral, de maladie coronarienne, d’insuffisance cardiaque congestive et de mortalité totale. Alors que les thiazides sont les plus couramment utilisés, les diurétiques de l’anse

sont également utilisés avec succès et l’association avec un diurétique d’épargne potassique réduit le risque d’hypokaliémie et d’hypomagnésémie. Même à petites doses, les diurétiques potentialisent d’autres antihypertenseurs. Le risque de mort subite est réduit lorsque des diurétiques épargneurs de potassium sont utilisés. À long terme, les spironolactones réduisent la morbidité et la mortalité chez les patients souffrant d’insuffisance cardiaque

c’est une complication typique de l’hypertension de longue date.

Bêta-bloquants:

Un tonus sympathique élevé, l’angine de poitrine et un infarctus du myocarde antérieur sont de bonnes raisons d’utiliser des bêtabloquants. Étant donné qu’une faible dose minimise le risque de fatigue (un effet désagréable du blocage b

l’ajout d’un diurétique ou d’un inhibiteur calcique est souvent bénéfique. Cependant, le traitement par blocage b estassociée à des symptômes de dépression, de fatigue et de dysfonction sexuelle. Ces effets secondaires

doivent être pris en considération dans l’évaluation des avantages du traitement. Au cours des dernières années, les b-bloquants ont été utilisés de plus en plus fréquemment dans la prise en charge de l’insuffisance cardiaque, complication connue de l’hypertension artérielle. Ils sont efficaces mais leur introduction en présence d’insuffisance cardiaque doit être très prudente, à commencer par des doses très faibles pour éviter une aggravation initiale de l’insuffisance cardiaque. Bloqueurs des canaux calciques Les bloqueurs des canaux calciques peuvent être divisés en dihydropyridines (par exemple nifédipine, nimodipine, amlodipine) et non-dihydropyridines (vérapamil, diltiazem). Les deux groupes diminuent la résistance vasculaire périphérique mais le vérapamil et le diltiazem ont des effets inotropes et chronotropes négatifs. Les dihydropyridines à courte durée d’action telles que la nifédipine provoquent une activation sympathique réflexe et une tachycardie, tandis que les médicaments à longue durée d’action tels que l’amlodipine et les préparations à libération lente de nifédipine provoquent moins d’activation sympathique. Les dihydropyridines à courte durée d’action semblent augmenter le risque de mort subite. Cependant, l’essai sur l’hypertension systolique en Europe (SYST-EUR) qui comparait la nitrendipine au placebo a dû être arrêté tôt en raison des avantages significatifs

thérapie. Les inhibiteurs calciques sont efficaces chez les personnes âgées et peuvent être sélectionnés en monothérapie pour les patients atteints du phénomène de Raynaud, de maladie vasculaire périphérique ou d’asthme, car ces patients ne tolèrent pas les b-bloquants. Le diltiazem et le vérapamil sont contre-indiqués dans l’insuffisance cardiaque. La nifédipine est efficace dans l’hypertension sévère et peut être utilisée par voie sublinguale; il faut faire preuve de prudence en raison du risque d’hypotension excessive. Les bloqueurs des canaux calciques sont souvent associés aux b-bloquants, aux diurétiques et / ou aux inhibiteurs de l’ECA.

Inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion de l’angiotensine:

Les inhibiteurs de l’ECA sont de plus en plus utilisés comme traitement de première intention. Ils ont relativement peu d’effets secondaires et de contre-indications, à l’exception des sténoses bilatérales de l’artère rénale. Bien que les inhibiteurs de l’ECA soient efficaces dans l’hypertension rénovasculaire unilatérale, il existe un risque d’atrophie ischémique. Par conséquent, l’angioplastie ou la reconstruction chirurgicale de l’artère rénale sont préférables à une thérapie purement médicale à long terme. Les inhibiteurs de l’ECA sont des agents de premier choix chez les patients hypertendus diabétiques car ils ralentissent la progression de la dysfonction rénale. Dans l’hypertension avec insuffisance cardiaque, les inhibiteurs de l’ECA sont également des médicaments de premier choix. L’essai HOPE a montré que le ramipril réduisait le risque d’événements cardiovasculaires même en l’absence d’hypertension. Ainsi, cet inhibiteur de l’ECA peut exercer un effet protecteur par des mécanismes autres que la réduction de la pression artérielle. Bloqueurs des récepteurs de l’angiotensine II Comme l’angiotensine II stimule les récepteurs AT1 qui provoquent la vasoconstriction, les antagonistes des récepteurs de l’angiotensine AT1 sont des antihypertenseurs efficaces. Le losartan, le valsartan et le candésartan sont efficaces et provoquent moins de toux que les inhibiteurs de l’ECA. L’étude LIFE est le plus récent essai historique sur l’hypertension. Plus de 9000 patients ont été randomisés pour recevoir soit le losartan, un antagoniste des récepteurs de l’angiotensine, soit un b-bloquant

(aténolol). Les patients du bras losartan ont présenté une meilleure réduction de la mortalité et de la morbidité, en raison d’une plus grande réduction des AVC. Le losartan a également été plus efficace pour réduire l’hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche, un puissant facteur de risque indépendant d’effets indésirables. Chez les patients souffrant d’hypertension systolique isolée, la supériorité du losartan sur l’aténolol était encore plus prononcée que chez ceux souffrant d’hypertension systolique et diastolique. Ces résultats favorables ont conduit à un éditorial intitulé: «Blocus de l’angiotensine dans l’hypertension: une promesse tenue». Il convient de noter que le comparateur de l’étude LIFE était un b-bloquant et que, dans le passé, les b-bloquants n’étaient pas meilleurs que le placebo chez les personnes âgées.

Bloqueurs a1-adrénergiques Exempts d’effets secondaires métaboliques, ces médicaments réduisent le cholestérol sanguin et la résistance vasculaire périphérique. La prazosine a une action plus courte que la doxazosine, l’indoramine et la térazosine. Ces médicaments sont hautement sélectifs pour les récepteurs adrénergiques a1. La somnolence, l’hypotension orthostatique et parfois la tachycardie peuvent être gênantes. La rétention d’eau peut nécessiter l’ajout d’un diurétique. La phénoxybenzamine est un agoniste des récepteurs a-adrénergiques non compétitif utilisé (en association avec un b-bloquant) dans la prise en charge des patients atteints de phaéochromocytome, bien que récemment la doxazosine ait été utilisée avec succès. Vasodilatateurs directs:

L’hydralazine et le minoxidil sont des vasodilatateurs à action directe. Leur utilisation a diminué en raison du potentiel d’effets secondaires graves (syndrome du lupus avec l’hydralazine, hirsutisme avec le minoxidil). Inhibiteurs adrénergiques centraux La méthyldopa est à la fois un faux neurotransmetteur et un agoniste des récepteurs adrénergiques a2. La clonidine et la dexmédétomidine sont des agonistes des récepteurs a2-adrénergiques situés au centre. La sélectivité pour les adrénorécepteurs a2 vs a1 est la plus élevée pour la dexmédétomidine (1620: 1), suivie par la clonidine (220: 1), et la moins pour l’a-méthyldopa (10: 1). La clonidine et la dexmédétomidine rendent la circulation plus stable,

réduire la libération de catécholamines en réponse au stress, et

provoquer une sédation telle que la dexmédétomidine est maintenant utilisée pour la sédation dans les unités de soins intensifs.

La moxonidine est représentative d’une nouvelle classe d’agents antihypertenseurs agissant sur les récepteurs de l’imidazoline1 (I1). La moxonidine réduit l’activité sympathique en agissant sur les centres de la rostrale ventrale

médullaire latérale, réduisant ainsi la résistance vasculaire périphérique.

Peptides natriurétiques:

Les peptides natriurétiques jouent un rôle dans le contrôle du tonus vasculaire et interagissent avec le système rénine-angiotensine-aldostérone. En inhibant leur dégradation, les inhibiteurs de la peptidase rendent ces peptides naturels plus efficaces, réduisant ainsi la résistance vasculaire. Cependant, il n’y a que des essais à petite échelle de leur efficacité. Dans l’ensemble, des études récentes n’ont pas réussi à démontrer la supériorité des agents modernes sur les médicaments plus traditionnels, sauf dans des circonstances particulières, comme l’a démontré une méta-analyse basée sur 15 essais et 75 000 patients. Chez de nombreux patients, un traitement efficace est obtenu par l’association de deux agents ou plus, avec un gain d’efficacité et une réduction des effets secondaires.

Gestion des risques